Our increasingly inequitable relationship with tech and social media

Whose interests are they serving and how do we get some agency back?

I did not mean this to be my first post of 2025. It has been sitting in my drafts for a while as I try to make sense of the tangled web of thoughts in my head about the benefits and perils of social media, in a world that is increasingly fraught with misinformation, disinformation and resultant polarisation and where it seems like we are fast losing our agency over what we pay attention to, and as a result what we care about.

However, the recent news from Meta brought it back for me with renewed urgency. I wanted to reflect on the literature I had read that helps posit ways of regaining a semblance of control, but also have a way of getting my questions out about what we want from social media and whether we have any agency in bringing about the changes that are deeply and swiftly necessary to make it safer, more productive and more fun.

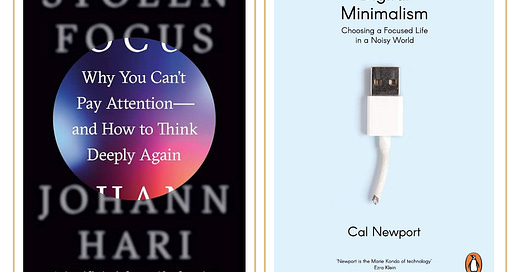

Cal Newport’s ‘Digital Minimalism’ was something I picked up by chance in 2020. It seemed like the optimal time to read that kind of book - when it felt like on the macro scale, too much was happening while in my micro, very little was changing.

I wanted to take stock and understand how much damage my awful social media dependency was doing to me. Unsurprisingly, it turned out that it was a fair amount. If you have ever been curious about how you can build a healthier relationship with social media, and importantly, why you should, I would highly recommend it.

It opened my eyes to how social media has used neuroscience to specifically make its products addictive. In this incessant attention economy, the more time we spend on these platforms, the more lucrative a customer we are. Cal Newport talks about two principles that social media leverages to enable them to keep us staring at our screens:

Unpredictable Reinforcement: This is the phenomenon of a reward being more potent and powerful when it is unexpected than when it is expected such as a like or a comment.

Social Proofing: As Aristotle rightly said, man is a social animal. And we have largely relied on social proofing - being liked and accepted by a group - for our survival, historically.

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram and X lean on these principles to deliver on attention engineering - which is making the app as attractive to us as possible so we do not want to leave. For those who have read Percy Jackson, it sounds a lot like the Lotus Casino.

Luckily, after making you feel pretty awful about how you are essentially trapped in an endless cycle of posting, watching other people post curated stories of their lives and cherishing the false sense of intimacy you are made to feel, Newport offers some helpful tips on how you can manage your behaviours to use social media in ways that are healthy. The ones I found most helpful were:

Use digital technologies in a purpose-driven way rather than using them just for the sake of using them.

Come up with rules for everything you use and write them down to create accountability.

Remember that apps on your phone are designed to be more addictive than the browser versions of the apps.

We reach for our phones out of habit and end up filling our time unnecessarily with technology. So, make sure there are other activities you can and want to do in your leisure time.

The way I have altered my behaviour across my social media and tech usage is through introducing certain habits and rules based on this advice. This meant doing a digital decluttering by unfollowing the people whose lives I didn’t need to know about, taking apps like Instagram off my phone for a couple of years so I could develop a more sensible relationship with the app, and making use of the ability to uninstall and reinstall the apps so I can use my time more wisely.

While Cal Newport’s book focuses on how there are systems at work that create our social media addictions and dependencies, it very much focuses on the individual ways by which we can counter this. ‘Stolen Focus’ by Jonah Hari takes a different approach, focusing on the macro and systemic rather than just the micro and individual.

I discovered ‘Stolen Focus’ through Rebel Book Club, which is a community of non-fiction readers. This book discusses attention loss and the loss of focus as the result of a multitude of factors from the stressful and fast-paced lives we lead, to the algorithms that increasingly dictate our lives.

What became apparent to me is that while Cal Newport book was massively empowering in helping me to take back some agency, it is scary to think to what extent we are still in control of our own lives and to what extend they are being governed by algorithmic forces that operate in black box environments we can’t disentangle ourselves from nor understand, let alone control. It is the individual against a rigged system and so then how can you help but fail?

A spine-chilling quote from the book that I think about all the time shows how the people who are tasked with designing these apps to be more addictive and involving do not want to live in the world they are creating.

“One day, James Williams – the former Google strategist I met – addressed an audience of hundreds of leading tech designers and asked them a simple question. ‘How many of you want to live in the world you are designing?’ There was a silence in the room. People looked around them. Nobody put up their hand.”

If that is not a true indictment of these platforms, I don’t know what is.

These algorithmic forces may be designed to be “neutral”, however because of the natural negativity bias that is ingrained in human beings, a feed which has negative, angry content is more likely to hold our attention. Therefore, negative content is rewarded at a greater rate than positive content, despite supposed algorithmic neutrality.

On YouTube, what are the words that you should put into the title of your video, if you want to get picked up by the algorithm? They are – according to the best site monitoring YouTube trends – words such as ‘hates, obliterates, slams, destroys’.

Beyond making negative content more visible, studies are showing these algorithms are likely to increase anti-social sentiment and behaviour like misogyny. A 2024 study from Dublin City University found that the recommender algorithm pushed extremist misogynistic content to perceived male profiles regardless of whether they were seeking this kind of content.

All this is made more difficult not only by the algorithms, but when the shifting winds of politics encourage a more “Wild West” approach. With our attention in the hands of tech billionaires who swing as eagerly as the loosest weather-vanes, we get decisions like the one made by Mark Zuckerberg in early January of this year that Meta is going to stop working with third-party fact-checking organisations.

It is obviously no mystery as to why Zuckerberg has followed in the footsteps of Elon Musk in removing fact-checking from Meta apps. Ingratiating himself to President Trump seems to be the foremost of his priorities. This is a massive U-turn from Meta’s behaviour in 2021 which saw the platform suspend Trump’s accounts after he praised his supporters for their appalling behaviour when they stormed the US Capitol. It is unsurprising then that President Trump has it out for Zuckerberg, having threatened to sentence him to a “lifetime in prison.” But Zuckerberg is one of the many tech CEOs who are bowing down obsequiously to Trump - with Apple, Amazon, Meta and Google being among the many who have donated to Trump’s inauguration ceremony, raising over $200 million.

If this is not sickening enough, Meta has not only decided to end third-party fact checking from Meta’s platforms, but along with this has removed policies related to anti-LGBTQ+ hate speech. This is alarming because far from protecting communities who will already be marginalised by the Trump administration, they will allow and encourage hateful and anti-LGBTQ+ content to be disseminated.

The discomfort for me also arises because as a part of the marketing industry, I endorse, encourage and benefit from the use of these apps - particularly when that usage is more than it should be. While the industry has become much more cognisant of the role it plays in this space, with institutions like the Conscious Advertising Network who seek to be the (very much-needed) conscience within the commercials of the UK advertising industry, there is always more that brands, creative agencies and media agencies can and should be doing in order to safeguard communities.

As consumers, we should not have to be plagued with moral dilemmas about whether to use certain social media apps to counter the behaviour and decision-making of its irresponsible owners. Social media has been a hugely important for people’s careers, to allow people to stay in touch with and reconnect with friends and family, to provide people with an alternate source of news when news media fails to provide accurate information and coverage, etc. However, in the absence of being able to rely on governments to effectively challenge tech companies, and on tech CEOs to make decisions in the best interests of their society and their users, what are the options we have?

‘You don’t even really get to make that ethical decision’ to improve people’s attention spans, Tristan realised, ‘because your business model and your incentives are making that decision for you’. Years later, testifying before the US Senate, he explained: ‘I failed because companies don’t [currently] have the right incentive to change.’

In an ideal world, our media would be well and truly ours, in the hands of the public and serving public interests rather than the agendas of fickle billionaires and corrupt governments. But in the absence of this, there are people who are picking up the responsibility of creating more agency for social media and tech consumers. A great example of this is the Calm Tech Certified Program. Created by UX designer Amber Case, the certification seeks to be the “the world’s first standard for attention and technology”, evaluating whether the tech product is in service of people’s attention and time, or something that works against it.

This is really an incomplete rumination for changes in this space happen so quickly. But ultimately the hope is that we go into using these apps with our eyes wide open about the agendas that they have, and make sure we are using them in a way that serve us and not the other way around.